Home About Robert CV The Good Lord Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: Pentimento Memories of Mom and Me Novels Reviews ESL Papers (can be viewed online by clicking on titles) The Many Roads to Japan (free online version for ESL/EFL teachers and students) Contact

|

Introducing Discussion Skills to Japanese University Students Revisited (2): More

Practical Lesson Plans

Robert W. Norris

Keywords: ESL, EFL, discussion skills, critical thinking, lesson plans

Abstract

Based on the ideas for implementing critical thinking elements into an English discussion skills class at a Japanese university outlined in a previous paper (Norris, 2014), this paper provides some comprehensive lesson plans for teaching basic discussion skills. Each plan involves two phases: (1) a review of key vocabulary, expressions, and patterns commonly found in the exchange of opinions, reasons, agreement, disagreement, turn-taking, and compromise and (2) cued dialogues that lead students toward weighing both sides of a topic and learning simple ways of compromising.

Introduction

The first paper (Norris, 2014) of this two-part series consisted of four parts: (1) a discussion of Fukuoka International University's (FIU) Life Skills Education Policy; (2) a review of research I did and recommendations I made on teaching discussion skills to lower-level Japanese junior college students in the 1990s; (3) a summary of relevant research related to the teaching of critical thinking and discussion skills in Japan; and (4) an explanation of the rationale for the revision of my discussion skills class in order to follow FIU's new Life Skills Education Policy. It also included some introductory lesson plans for teaching discussion skills.

This paper follows up with several comprehensive discussion skills lesson plans. As recommended in previous papers (Norris, 1996; 1997; 2014), the lesson plans are based on an understanding of Japanese communicative style, an awareness of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) research, and a systematic approach. The approach itself is based in part on Littlewood's (1981, 1992) methodological framework for teaching oral communication and incorporates portions of the direct approach to CLT, which is seen as well suited to the type of learning background most Japanese students bring to college and university classes.1 The approach involves two phases for each lesson plan: (1) a review of key vocabulary, expressions, and patterns commonly found in the exchange of opinions, reasons, agreement, disagreement, turn-taking, and compromise and (2) cued dialogues that lead students toward weighing both sides of a topic and learning simple ways of compromising (see Appendix 1).

There are always potential problems that can arise in trying to get all students to participate in English discussions actively. Students will often revert to their native language when they don't understand something or don't know how to say what they want to say in English. For teachers who encounter such problems, Venema (2006) provides a detailed list of where and why discussions often break down and what the teacher can do to improve student participation. The important thing is for the teacher to show a lot of patience in guiding the students toward becoming accustomed to the rhythm and flow of English discussion and gaining confidence in expressing themselves. Constant encouragement to use such classroom English expressions as "How do you say in English?" and "What does mean?" is also needed to get the students to help each other and stay in the target language as much as possible. In each of the lesson plans below, there is no set time schedule to follow. Depending on the level and motivation of the class, each lesson may take a few hours to complete or may be completed in a single 90-minute session.

Odd Man Out2

After doing some previous lessons involving simple exchanges and practice of expressing opinions, giving reasons, agreeing, and disagreeing, I usually use this discussion activity first in introducing students to how to compromise on a single plan. I hand out a series of lists (see Appendix 2) of items in one category such as fruit, countries, animals, parts of the body, clothes, and musical instruments. From each list, students must choose one item that is special, unique, different, or has a characteristic the others in the list don't have. This one item is the Odd Man Out.

I encourage students to use their imaginations rather than choosing the obvious in explaining the reasons for their choices. An example of this would be choosing the reason for the Odd Man Out in a fruit list comprised of apple, orange, mango, banana, grape, and peach. Many students would choose the banana because it is the only one that is long while the others in the list are round. I demonstrate that an added reason could be that the banana is the only one that has no letters that extend below the line the word is written on. All the other fruit names contain a "p" or a "g," both of which extend below the line.

I first put the students in groups of two or three and have them choose who starts (a quick round of paper, scissors, stone works well). I let the students use their list of various expressions and tell them to try to follow the four-line model discussion pattern introduced earlier (see Appendix 1). I then introduce some new and useful expressions for explaining reasons: "It is the only one that "; "all the others "; "they are alike/similar because "; and " is the same as/different from because ."

If one or more groups finish ahead of the others, I ask them to create two or three more lists of their own and continue practicing. Also, once the groups have worked hard and compromised on the lists, I often pit teams against other teams and ask them to change all pronouns from singular to plural (e.g., "I think that " to "We think that "). I've found that once a team has completed a plan, the members often become emotionally invested in that plan and work even harder to defend their plan when discussing it with another group. This creates an intrinsic motivation for the students to be more active in practicing the patterns for adding reasons, politely disagreeing with others' opinions ("I see your point, but "), and pointing out the weaknesses in the others' reasons. It also helps students make a connection between creative thinking and negotiating.

If there is time, representatives from each group can come to the front of the class and explain their opinions and reasons to the rest of the class.

Best Ways to Use Free Time3

This discussion topic also requires the students to compromise. I give the students a list of possible ways to use free time and a list of possible reasons. I use a variation of the lists provided in Seido's Modern English Cycle Two: Discussions (see Appendix 3). Before beginning, I review previously studied expressions, as well as new vocabulary. Students can use any of the ways to use free time and reasons included in the lists, but they must also think of one or two of their own ideas. Person A's initial opinion pattern can be provided to help the groups get started: "In my opinion, ing should be one of the five best ways to use free time." An "if" conditional pattern for explaining reasons can also be demonstrated: "If you [present tense verb], you can [infinitive form of verb]." The full demonstration would be like the following.

In drawing students' attention to the "if" conditional, I point out that the idea used in the opinion (i.e., reading books) can be used in the "if" clause. I also stress the importance of using "you can" versus "I can" as a good strategy to convince others of the benefit they receive rather than how it helps the speaker personally. This "you can" result clause should be added to the expressions for giving reasons that the students have been introduced to previously. This is also a good time to review the criteria for what constitutes a good reason. I include four kinds of reasons adapted from LeBeau, Harrington, and Lubetsky (2000): examples (i.e., things you have experienced, heard, or read); common sense (i.e., things that you believe everyone knows); expert opinion (i.e., opinions of experts - this requires research); and statistics (i.e., numerical facts - this also requires research). In terms of what kind of reasons go well with what kind of opinion types, I point out that factual statements go well with opinions of comparison ("John is a better batter than Bill. John hit 22 home runs, but Bill hit only 10."); "if" conditionals go well with "should"-type opinions ("He should stop smoking. If he stops smoking, he will be healthier.").

While students are preparing their opinions and reasons individually, I walk around giving help where needed. I often will give a time limit to find five items with corresponding reasons. After most students have come up with at least two or three items, I put them in pairs to begin trying to compromise on a single set of five ways to use free time. I tell the students who have not yet completed all five ways that they must ad lib the remaining number without preparation. Again, I walk around helping students, making sure they are following the model and using the various expressions correctly, and sometimes playing the devil's advocate in order to prod them into thinking more creatively.

When the pairs have compromised on five ways of using free time, I have them next rank the five ways in order of importance. I give them a model opinion sentence: "[opinion expression], ing should be the best / second best / third best / fourth best / fifth best way to use free time." When all the groups have completed their rankings, I pit teams of two or three members against other teams to come up with a single list of five and its ranking. This is usually when things get interesting. All the groups have invested a lot of work in compromising on a plan and are more likely to have different opinions from other groups. They often become quite stubborn in defending their ideas, which leads to more active and animated practice in the areas of adding reasons without preparation, disagreement, and pointing out weaknesses in the reasons of the other groups. When some teams run out of ideas for reasons, I show them how to use the expressions for compromising. If both sides in the discussion are too stubborn to compromise, I demonstrate that they can simply say, "Let's go on to the next item and come back to this later."

Marriage or Career?4

The next discussion topic continues in giving students practice in the creative and critical thinking required for giving reasons for their opinions. I give the students a handout (see Appendix 4) with information on a career woman named Pam who has received three different marriage proposals and is faced with giving an answer to each suitor, as well as with deciding whether to continue her working career or not. The handout provides basic background information on her job, her personality, and characteristics of the three suitors. I take some time to check students' understanding of vocabulary and the situation.

Before beginning the discussions in pairs, I have the students individually make lists of the best and worst characteristics of each suitor, as well as the advantages and disadvantages of each option. Students must also make lists of their imagined consequences for each option. Again, the "if" conditional is a useful pattern. For example, "If Pam marries Bill, she will / won't / can / can't / might + [infinitive verb] + because [reason(s)]." When an allotted time has passed for this preparation, I put the students in pairs (or groups of three in a large class) and have them exchange opinions and reasons on the suitors' characteristics, the advantages and disadvantages of each of Pam's options, and their ideas on imagined consequences of each option. I also have the students put checks by every expression they use or hear on their expressions list. There is no need to compromise at this stage. After the students have done this practice for a certain amount of time, I break up the original groups and put them into different pairs with the goal of compromising on one plan of action for Pam. I provide the opening opinion pattern of "[opinion expression] + Pam should marry [name of suitor]" or "[opinion expression] + Pam should continue working."

When all pairs have finished compromising, I again pit teams against each other. Having walked around and listened in on their discussions, I try to match teams with different opinions against each other. If some pairs finish more quickly than others, they can be asked to summarize their discussions in writing or verbally to the teacher while the others are finishing up.

Whom Do You Lay Off?5

This is a more complicated type of discussion that requires students to think more deeply about causes, results, and consequences than the previous discussion concerning marriage versus career. I give the students a handout (see Appendix 5) describing a situation in which they are a boss at a car factory and, because of a severe budget cut, the company must lay off one of four assembly line workers. The qualifications and characteristics of the four workers are included in the handout.

Before beginning the main discussion of whom to lay off, I give the students time to evaluate carefully the various worker qualifications and characteristics. The purpose of this is to help them in clarifying the reasons for their opinions. I have the students answer the following three questions and prepare reasons for each answer.

In addition, I ask the students to write down what they think might happen to each worker if that worker loses his or her job. This provides good practice and repetition in reviewing conditional sentence patterns, as well as stimulating the students to engage in the critical thinking area of imagining consequences of actions. It may even encourage them in developing the ability to express feelings of empathy in English.

The next step is to place students in pairs or groups of three to exchange opinions and reasons for the above questions. The focus is on using the various expressions they have been exposed to while agreeing, disagreeing, explaining and adding reasons, giving signals, and turn-taking. If the students still need help in what patterns and expressions to use in order to start the discussions, I provide the first line. Some examples are below:

This step seems to help give the students more confidence for when they have to give reasons for their opinions in the next stage. After these exchanges are completed, I mix the students into different pairs or groups of three and have them begin the main discussion of which worker to lay off.

Before having the new teams dive headfirst into trying to compromise on which worker to lay off, I first have them discuss and agree on what the company employment policy should be. I refer them back to the opinions they expressed on what they thought were the important characteristics for the job. The groups should decide on a list of at least three required qualifications and characteristics, as well as why they are important. I prompt the students to think about such areas as loyalty, health, personality, work habits, education, length of service, and family responsibilities. Students can refer back to the handouts that contain details on each of the four workers. A sample opening opinion model can be: "[Opinion expression], our company employment policy should include ." Reasons can be explained with "if" conditional sentences. Students should be reminded that their later decisions of whom to lay off and whom to keep must be based on their agreed-upon company employment policy.

Once the students have agreed upon a company employment policy, they begin the main discussion on which worker to lay off. If some groups compromise more quickly than others, I ask them to continue their discussion by considering the following questions:

When the first round of compromises is finished, teams are again pitted against each other. If time permits, representatives from each group can also be asked to come forward and present their decisions and reasons in front of the class.

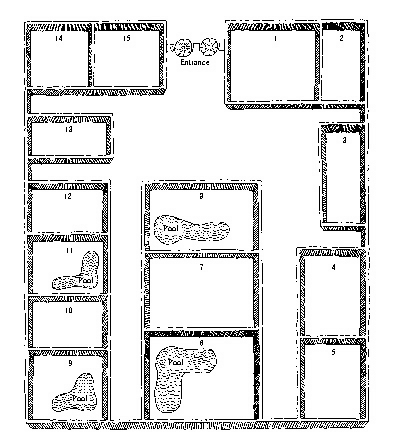

Zoo Plan6

After having done a few lessons involving extended dialogues and compromising, I next introduce a discussion skills unit that has the students create a zoo plan. I tell the students they are the managers of a zoo that has 15 cages of varying sizes. Four of the cages have pools. I call on individual students to brainstorm animals for each of the 15 cages -- 11 cages for land animals and four for water animals. I also ask how many of each kind of animal they want. The resulting list may look something like this:

I then check to make sure all the students know the names and kinds of animals before handing out the same zoo layout (see Appendix 6) to each student. I give the students some time to decide individually which cages they want to put the different animals in and why. After that, I put the following cued dialogue on the board:

I put the students into pairs with the task of compromising on a single zoo plan with reasons for each choice of cage. Students often need some guidance in forming logical reasons for their opinions, so I demonstrate how to link the special characteristics of a cage with the special characteristics of a particular animal in order to have a convincing reason for an opinion.

The example I often use is pointing out that cage number one is large and near the entrance, while elephants are also large and popular. The cage and the animal are suited to each other because elephants need a large space and since they are popular animals, they can attract more customers by being placed near the entrance. Students often use reasons that take into consideration the characteristics of only the animal or only the cage. I usually take time to review expressions for either disagreeing or agreeing partially ("That may be true, but "; "I see your point, but "; etc.) at this stage and demonstrate how the students should add their own differing opinion after the expression.

Students now begin the task. I walk around helping with vocabulary, prodding the students to use as many previously learned expressions as they can in reacting to each other, and playing the devil's advocate. I allow the students to use their notes to refer to when they have difficulty in remembering key expressions. After a few cages have been decided upon, I ask the students to put their notes away, try to use the same expressions from memory, and help each other if they still have trouble.

Some pairs may finish the zoo plan quickly because the students tend to agree with each other easily, but others will spend more time in working out their plan. While some pairs are still trying to compromise, I tell the early finishers to start writing down the reasons for their cage choices. That makes it easy to determine what areas need more work and to give individual attention.

The following is an example of a compromise that might be made at this stage:

After these first plans are made, I assign everyone to write down their reasons as homework. Before beginning the next stage, I look at the reasons the students have written and give some help with grammar, vocabulary, and word choice. The next stage is to have pairs work with other pairs with the task of compromising on a new zoo plan. This is where the activity usually takes off. Because the original pairs have worked hard to create the initial plan and have formed their opinions and reasons together, they work hard to defend their plan. The odds are slim that any pair will have the exact plan as another pair. There are usually several exchanges of opinions before a compromise on any cage is made. If the students get stuck on one cage and cannot compromise, they can simply say "Let's go to the next one" and come back to that cage later. If all but a few cages have been compromised on and the pairs cannot seem to agree on the final ones, I help the students out by writing the pattern for the first conditional (i.e., "If + [subject] + [present tense verb], [subject] + will / won't / can / can't / might / might not + [infinitive verb]") on the board and demonstrating that in the case of a stalemate it is possible to compromise by trading one cage for another: for example, "If you put the zebras in cage number three, we'll put the koalas in cage number seven."

When nearly all the groups have compromised on a plan, secretaries from each group can be asked to write the results on the board so each group can compare its plan with the other plans. If time permits, a reporter from each group can be asked to explain the reasons for the group's choices.

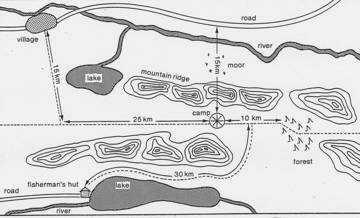

Lost7

In this discussion lesson, I ask the students to think of a variety of possible courses of action and compromise on the best one. I give the students a handout that has a description of a teacher on a hiking trip with some students. The group has become lost in some highlands and is in trouble (see Appendix 7). A map is included with the handout. Students must first individually read the situation, check new vocabulary, and brainstorm a given number of possible plans to save the hikers.

After brainstorming some ideas, the students next make a list of advantages and disadvantages for each plan. During this pre-discussion stage, I walk around giving students individual help with vocabulary and acting as a devil's advocate to prod them into thinking through the possible results of their plans of action. This is a good time to demonstrate again expressions for partial agreement, give an opposing opinion, have the student ask for my reason, explain my reason by using an "if" conditional showing the limitations of the student's idea (e.g., "If we use your idea, we'll have this bad result. If we use my idea, we'll have this good result."), give the signal ("Wouldn't you agree?") to show I'm finished explaining, and show how the student can compromise ("I didn't think of that before. You're right. I agree.") if he or she is convinced my reason is better than his or hers. This is an important step to take because finding opportunities to practice how to compromise is a lot more difficult than it is for practicing expressions of agreement, disagreement, and turn-taking.

When all the students have come up with at least one or two ideas for saving the hikers, I put them in pairs to exchange opinions, give reasons, and compromise on a single plan that they will defend later against another team. If some pairs finish quickly, they can be asked to write down a summary of their discussion. The mistakes found in these summaries can be used for review of vocabulary and patterns at a later date. The final stage of this lesson is to have teams discuss their plans with other teams and once again come up with a compromise solution. I try to pit teams that have different plans against each other in order to ensure a more lively discussion that forces them to use the full array of discussion expressions.

Conclusion

The lesson plans presented in this and the previous paper (Norris, 2014) are designed to introduce Fukuoka International University's Modern English Course students taking a discussion skills class to some of the life skills areas recommended in FIU's new curriculum that was adopted in 2012. In attempting to abide by FIU's Life Skills Policy recommendations (see Norris, 2014) and apply them to the discussion skills class, I have given priority to two main areas: (1) using elements of the direct approach to Communicative Language Teaching (see Dornyei and Thurrell, 1994), that employ task-based activities and require active participation by the students and (2) increasing student motivation by linking the discussion topics as closely as possible to the students' own lives and concerns.

Concerning the first priority, the key elements include Dornyei and Thurrell's (1994) ideas for specific language input (e.g., discussion expressions list in Appendix 1), increasing the role of consciousness-raising (e.g., providing specific patterns and models, as well as explanations of their functions within the discussion tasks), and sequencing communicative tasks systematically (e.g., starting with simple exchanges of opinions, moving on to giving reasons for opinions, and eventually working toward compromising on a plan or on a resolution to a problem).

Concerning the second priority, motivating university students in an English as a Foreign Language (EFL) setting is by no means an easy task. Krieger (2005) believes that many EFL students might not care about learning English if they think it has no practical significance in their lives:

Through many years of trial and error, I have settled on the discussion topics listed in this paper because they seem to come close to being connected to the students' lives. Most of the students who have taken my discussion skills class have been either 3rd- or 4th-year students who are in the midst of the pressures of job-hunting. They seem to empathize greatly with the character of Pam in the "Marriage or Career" topic and the four assembly line workers in the "Whom Do You Lay Off?" topic. The "Zoo Plan" topic seems to be appealing as it involves animals that the students get to choose. Without fail, this topic has through the years been the one most actively and passionately discussed. The "Lost" discussion also produces a lot of active participation. This may be in part because in Japan there are a lot of natural disasters such as typhoons, floods, mudslides, volcano eruptions, and earthquakes that involve search parties that try to find missing people. These stories are often in the news and some students may even have had a personal experience of disaster or know someone who has been involved in a disaster.

As detailed in the previous paper (Norris, 2014), FIU's Life Skills Education Policy is based on the World Health Organization's 1997 publication Life Skills Education in Schools. The key skills the WHO focuses on are critical thinking, creative thinking, decision-making, problem-solving, effective communication, interpersonal relationship skills, self-awareness, empathy, coping with emotions, and coping with stress. Through the medium of discussion practice in English, the lesson plans included in this paper touch upon at least an introduction to almost all these key skills.

Given the limited number of times students and teachers in college and university classes meet in a school year in Japan, the overall goal of the activities and instruction discussed in this paper is not to produce students capable of participating in debates and discussions beyond their current capabilities. The focus is on equipping the students with basic communicative competence, control over patterns and vocabulary, and confidence to become even more proficient in the future.

The activities in the two papers of this series have been presented in a sequence that takes the students from a review of forms they have learned before to a stage where they can develop a moderate degree of independence and participate in meaningful interaction. There is, however, no set formula to determine the teacher's selection of activities. Each class is different with different needs and abilities.

As teachers, we have at our disposal a tremendous amount of materials and activities for teaching. The lesson plans described here are meant to provide illustrations of activity types and how they can be carried out rather than to be prescriptive lesson plans. I am quite pleased with the responses I have had from students over the years, but I am continually refining the lessons from week to week in each class I teach. Not every class has been successful. A great amount of patience and a belief in the potential for positive results over the long haul are indispensable.

I hope the material included in this and the previous paper will help other teachers who are interested in or required to include critical thinking and other life skills elements in their English classes.

Acknowledgment

I would like to express my profound thanks to my colleague Professor Dominic Marini for his invaluable proofreading of this paper.

Notes

1. See Hyland (1994: 55-74).

2. The idea for "Odd Man Out" comes from Ur (1981: 48-49).

3. The idea for "Best Ways to Use Free Time" comes from Seido (1982: 40-41).

4. The idea for "Marriage or Career" comes from Byrd and Clemente-Cabetas (1980: 1).

5. The idea for "Whom Do You Lay Off?" comes from Byrd and Clemente-Cabetas (1980: 95).

6. The idea for "Zoo Plan" comes from Ur (1981: 81-83).

7. The idea for "Lost" comes from Klippel (1984: 104-105).

References

Brown, H. D. 2001. Teaching by Principles. New York: Longman.

Byrd, D. R. H. and Clemente-Cabetas, I. 1980. React Interact: Situations for Communication. New York: Regents Publishing Company, Inc.

Dornyei, Z. & Thurrell, S. 1994. Teaching conversational skills intensively: Course content and rationale. ELT Journal 48(1): 40-49.

Hyland, K. 1994. The learning styles of Japanese students. JALT Journal 16(1): 55-74.

Krieger, D. 2005. Teaching ESL vs EFL: Principles and practices. English Teaching Forum, (43) 2: 8-16.

Klippel, F. 1984. Keep Talking: Communicative Fluency Activities for Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

LeBeau, C., Harrington, D., and Lubetsky, M. 2000. Discover Debate: Basic Skills for Supporting and Refuting Opinions. California: Language Solutions, Inc.

Littlewood, W. 1981. Communicative Language Teaching: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Littlewood, W. 1992. Teaching Oral Communication: A Methodological Framework. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

Norris, R. W. 1996. Introducing discussion skills to lower-level students: Can it be done? Bulletin of Fukuoka Women's Junior College 51: 21-32.

Norris, R. W. 1997. Introducing discussion skills to lower-level students: Practical lesson plans. Bulletin of Fukuoka Women's Junior College 52: 9-23.

Norris. R. W. 2014. Introducing discussion skills to Japanese university students revisited (1): A life skills education perspective. Bulletin of Fukuoka International University No. 32: 1-16.

Seido Language Institute. 1982. Modern English Cycle Two, Book 8, Discussions. Japan: Seido Foundation.

Ur, P. 1981. Discussions That Work: Task-Centred Fluency Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Venema,

J. December 2006. Discussions in the EFL classroom:

Some problems and how to solve them. The

Internet TESL Journal, Vol. XII, No. 12.

World Health Organization. 1997. Life Skills Education in Schools. Programme of Mental Health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO.

Appendix 1 – Discussion Expressions

Expressing Opinions

Agreement

Disagreement

Compromise

Adding Reasons

Discussion ModelA: [opinion expression]

+ [opinion]

Appendix 2 – Odd Man Out

Sample discussion pattern

A: [Opinion expression] the should be the Odd Man Out B: “Why do you think so?” A: [Reason] + [Signal] B: Agree / Disagree

Lists

1. apple, orange, mango, banana, grape, peach 2. India, China, France, Uganda, United States, New Zealand 3. horse, cat, mouse, camel, lion, cow 4. finger, blood, heart, eye, muscle, tongue 5. sock, coat, dress, underpants, scarf, jeans 6. trumpet, drum, violin, flute, harp, piano 7. [Your own list] 8. [Your own list]

Useful expressions for giving reasons

It is the only one that All the others They are alike / different because is / are the same as / different from

Appendix 3 – Best Ways to Spend Free Time

Some possible ways to spend free time

1. Getting outside, fishing, picnics, gardening, etc. 2. Going to the movies 3. Reading books, studying 4. Watching entertainment programs on TV 5. Watching educational programs on TV 6. Listening to music 7. Going shopping 8. Taking up some hobby 9. Doing sports, jogging, or other exercise 10. Talking with friends 11. Getting involved in community activities 12. Helping the disadvantaged 13. Traveling, visiting places of historical or cultural interest 14. Doing some work different from your usual occupation 15. Getting a part-time job 16. Spending time with your family 17. Painting, playing a musical instrument, or taking up a similar artistic activity 18. Reading the newspaper 19. Spending time just thinking 20. Taking up a foreign language 21. Doing exciting things: motorcycle racing, water-skiing, etc. 22. Playing challenging games: chess, mahjong, etc. 23. Reading comic books

Some benefits of using free time well (possible reasons)

1. Keep up your physical strength 2. Relax your mind 3. Deepen or grow in knowledge 4. Expand your general education or cultural knowledge 5. Forget your cares for a while 6. Just relax 7. Just have fun 8. Be up-to-date on current events 9. Know the world around you 10. Make other people happier 11. Help people in need 12. Enrich your life 13. Refresh your body and spirit 14. Experience excitement 15. Understand other people 16. Deepen friendships 17. Calm your nerves 18. Discover a “new world” 19. Have a new experience 20. Be able to return to your work refreshed 21. Enrich your appreciation of art 22. Increase your powers of concentration 23. Develop new ideas or new approaches to problems

Appendix 4 -- Marriage or Career?

Pam is a beautiful and intelligent young career woman. She works at an international publishing company. Her job is editing writers’ books. Travel is an important part of her job, so she has already visited many parts of the world. Through her work and travel, she has met many single men who are interested in her romantically. Right now, she feels a little troubled because three men – Bill, Andrew, and Mike – want to marry her. She also feels a commitment to continue her career. She has the following options.

Option 1 -- Marry Bill

Option 2 -- Marry Andrew

Option 3 -- Marry Mike

Option 4 -- Continue her

career

Appendix 5 -- Whom Do You Lay Off?

You

are the supervisor of four assembly line workers at

the Modern Vehicles Auto Company. All the workers

make about the same salary. Because of a recent

budget cut by the board of directors, you have to

lay off one of the workers. The qualifications and

characteristics of each worker are listed below.

Appendix 6 – Zoo Plan Picture adapted from Ur’s Discussions That Work, Cambridge University Press, page 81

Appendix 7 – Lost

You are Sarah Harris, a 35-year-old teacher on a hiking trip in some highlands with a group of seven students. There are three boys and four girls between the ages of 13 and 16. You are carrying your own food and tents. You have planned to be out of contact with other people for a week. You are expected back on Sunday at a small town village on the west coast where you will be picked up by a bus.

Today is Thursday. It has been raining steadily since Tuesday night. Everyone is wet and cold. You know that you have not come as far as you should have come by this time. You start feeling worried about arriving at the meeting point on Sunday. During the morning, a dense fog starts coming down. Within a half hour, the mountains and the path are covered in thick fog. You have to walk by compass now. This slows down the group even more.

At lunchtime, two boys and two girls start complaining about stomach pains, diarrhea, and feeling sick. You think that some of the water you took from mountain streams may have been polluted. In the afternoon, the two boys and two girls feel worse and can walk only very slowly. While climbing down a steep hillside, the youngest girl, Judy, stumbles and falls. She cannot get up. Her leg is broken. You set up camp and discuss with your group what should be done.

You are in a valley between two mountain ridges. The nearest road is about 15 kilometers away in a straight line, but there is no path across the mountains and a moor is beyond them. There is no bridge across the river. Because of all the rain of the last few days, it may be too deep to wade across.

About five kilometers back the way you have come, a relatively easy path turns off and takes you to a lake and a fisherman’s hut about 30 kilometers away. However, you do not know if anybody lives in the hut or if it has a phone. The next village is about 40 kilometers away. About 10 kilometers back the way you have come, there is a small forest where you can probably find some firewood. You have enough food until Sunday and there are mountain streams nearby. You also have camping gas cookers and enough gas for three hot drinks and two warm meals a day, but there is no firewood. The only people who can read a map and use a compass, apart from you, are one of the sick boys and Joanne, the oldest girl (she is feeling OK). Judy is in a lot of pain and needs a doctor. What can you do?

Map from Klippel’s Keep Talking, Cambridge University Press, page 177

Copyright

(c) 1997-2021. Robert W. Norris. All Rights

Reserved

|